Wirral Borough Council’s Response to the New Ferry / Port Sunlight Explosion

Report written by Marion Grundy Ridewood on 17th June 2019

This report was presented to Wirral Borough Council cabinet members by the Justice for New Ferry group, who met with them on 17th June 2019.

The aim of the report was to tell cabinet members the truth, and to present to them all of the known facts that evidence the victims had not been helped at all by WBC, contrary to every press release that they had given since the explosion which stated they had supported the community.

It became necessary to write all this down and to inform council of the true facts, because in May 2019 there had been several public social media comments from members of WBC stating that the promised hardship fund would no longer go to the victims, but be used for general regeneration projects.

After they listened to all of the reports from the Justice for New Ferry group, many of the council cabinet ministers said that they were completely unaware that no support was given.

The following report is based upon the same 36 page report that was given to all council cabinet members on 17th June 2019.

The report was also sent to every single elected councillor in Wirral. It was also sent to James Brokenshire and Jake Berry in national government.

It details all of the failings (known at the time of writing) of Wirral Borough Council in the management of the emergency such that the victims received no help at all, other than to provide temporary emergency shelter for some of those made homeless.

It has been revised slightly only for the purposes of adding clarity where necessary, and to give updates pertinent to the council's hardship fund decision-making process. All revisions / updates are shown in square parentheses []

Wirral Borough Council’s Response to the New Ferry Port Sunlight Explosion

Report written by Marion Grundy Ridewood, 17/06/19, revised 18/07/19

Please feel free to download and read the report by clicking on the PDF icon

Alternatively, keep reading below.

Wirral Borough Council’s Response to the New Ferry Port Sunlight Explosion

Report written by Marion Grundy Ridewood, 17/06/19, revised 18/07/19

Report based upon the personal experiences of the victims and the local community, and upon factual evidence acquired from various sources including local and national authorities.

Contents

(Click on any section header to jump to that section.)

1. Introduction

Both local and national governments have persistently quantified the impact of the New Ferry / Port Sunlight explosion only in terms of its economic impact on the authorities. However, on 5th September 2018, I highlighted to James Brokenshire, Secretary of State for Housing, Communities and Local Government, that measuring the impact of the explosion should not simply be an exercise in calculating the costs to authorities.

Both to government, and in my report that followed (Grundy Ridewood, 2018), I stressed that the psychological, financial and welfare impact upon the victims is more important than the physical scale or the economic impact on the authorities because “these are people’s lives, and those lives are protected by the Civil Contingencies Act 2004”.

The impact of the New Ferry / Port Sunlight explosion upon the victims and the community was severe. One only needs to talk to the victims to be able to gain deeper understanding of the severity of the short and long-term impacts upon them. One can also put oneself in their shoes, imagine it was you, or your immediate family who were involved on that night.

Fig. 1 Private residence in Underley Terrace in which small children were sleeping upstairs (Echo, 2017)

Fig. 2 Restaurant full on the night before Mother’s Day, and small children sleeping upstairs (Echo, 2017)

Whilst there are many photos such as those above (Fig. 1 and Fig. 2) available all over the web, during the collection of impact statements, I was personally given photos from victims of the insides of their properties. As such, most of these images have not been seen before. They illustrate the severity of the destruction of their properties, and truly give one a deep insight and understanding of the utter devastation these victims felt both at the time of the explosion and upon being allowed to re-enter their homes and businesses: places which had previously brought them comfort, safety and income. These photos are given in Appendix A.

Please do look deep into these photos and imagine this was you. Know that in that moment of utter chaos, and in the weeks of chaos that followed, you are in a state of shock and in desperate need of help from those who are trained in such circumstances, and from those in authority whose legal responsibility it is to know exactly how to quickly provide all of the assistance you need in an emergency.

Addition for clarity: [The purpose of this report is (was) primarily to make council cabinet members aware of the failings of WBC and to evidence that the hardship fund, promised to assist the victims, must not be misappropriated, as had been alluded to by both the WBC press officer and a senior cabinet member publicly on social media during June and July of 2019.]

2. Personal Impact Statements & Victim Experiences

During August and September of 2018, I collected personal impact statements from those impacted by the explosion. As I was talking to people, collecting their photos and reading their statements, I was able to identify many common themes. Given that the number of statements collected was only few (57) considering the number of people impacted, these common themes were alarming.

Many of the discussions I had and the personal statements I collected, described events which clearly showed the victims did not receive the assistance that was expected, and some asked incredibly pertinent questions. A reminder of the excepts are given in Appendix B.

Through research of the government guidelines detailing the roles and responsibilities of local authorities in the event of an emergency given in 1) Recovery: An Emergency Management Guide (Home Office, 2016), 2) Emergency Response and Recovery (HM Government b, 2013) and 3) the Civil Contingencies Act 2004 (HM Government a, 2004), I was also able to identify many very serious questions that were raised by evaluation of the personal statements.

These questions, already published (Grundy Ridewood, 2018) are still in need of answers:

-

Why was the Bellwin Scheme not applied for within the first month?

-

Why did the homeless have to rely entirely on handouts of money, food and clothes from local charities or their own families?

-

Why was there no subsistence living expenses given to the homeless?

-

Why were the victims not directly and immediately given the monies donated to the council that was intended specifically to help them during those early weeks when they had nothing?

-

Why were new school uniforms not provided for the homeless children?

-

How was it possible for so many large and valuable items to be stolen from the secured zone when it had 24-hour manned security, particularly given the thefts continued even after they had been reported?

-

How is it justified to charge the victims for the emergency costs incurred by the council, and especially if they had no insurance cover?

-

David Ball publicly acknowledged the impact of closure on footfall and trade in a statement on 14/06/17 (Manning, 2017), so why has there been no quantification of or compensation for loss of trade?

-

Why has the community been left to cope entirely on their own financially and emotionally?

-

Why has New Ferry been allowed to stay in the same dishevelled state for 17 months with no regard for the impact on trade or the psychological impact on the community?

Key statements made (some hitherto unpublished) are:

Statement 1: “So after one and half months, the council gave us a house. But it was empty. It had no bedding, no cooking utilities, no cooker, nothing. We had to source all of these things ourselves. It was so hard at the beginning, when they refuse to help, you just feel so hopeless. The house we were put into was in such a bad condition. They had given it to us in such a limited time, but it wasn’t appropriate. So I told the council and Magenta. Both the council and Magenta admitted that the house was not in an appropriate condition for kids. So why did they put us in there in the first place? The council then moved us. But they gave us only one week’s notice. The new house wasn’t even decorated. It had no furniture, no cupboards, no curtains, the walls were rotten. It wasn’t ready to be lived in, it needed so much work. So I called the council, to see if they could help. They had given me only a week to fix this house they had provided, and they knew [we were both injured], so they could have sent people to help fix the house. But they refused to help. So the council rehomed me and my husband and my children, but they didn’t help at all other than providing an empty house. There was no help for furnishings or decorating, even though we had no money. During the week that we were still living in the inappropriate house, whilst making the new empty house habitable, the council forced us to pay rent on the two houses – the one we were in and the one I had to fix up to move into.”

Statement 2: “Life since the blast seems to have been one long argument with the utility providers, Conservation Officers, Council Officers all of them either being obstructive or demanding money with menaces.”

Statement 3: “After the first week, we wanted to know who would help, the council, the government, who would help us? I had so many meetings, trying to find out who could help me. One of them was with David Ball at the council. He told me that the council couldn’t help me because I had no insurance. I said “This is not my fault. If I had done this to my shop, then fair enough, but this is not my doing. Who is going to help me?” The council’s response was “Well this is not our fault either”. When you hear that, you feel angry.”

Statement 4: “The children did not even have school uniform for a month as we were relying on handouts from local charities which we were all incredibly grateful for”

Statement 5: “People were unable to buy things from shops as they did not have photographic I.D, credit and debit cards etc. as these had to be left within their homes and they were unable to access them. Banks were unable to give money for these reasons. One lady who came in, very embarrassed, to ask for clothes found a brand new, donated coat that fitted her. She broke down in tears as she had been wearing her father’s coat for several days and to have a coat that was not, obviously, a large gents coat was such a big issue for her. Families were living in 1 hotel room and teenagers were trying to revise for their exams under very difficult conditions. Many had lost their course work and feared they would be unable to complete their exams. Many found they were able to chat to the volunteers whilst looking for clothes as the centre was a ‘hub’ for people to meet others.”

Statement 6: “We had nothing at the B&B, no clothes, money or any belongings at all. At the B&B [a local shop owner] in New Ferry and other local people helped to gather us some clothes and a charity alongside Asda in Bromborough sent us shoes. We literally lost everything that night. We were advised to apply for the Wirral Council Local Welfare Fund shortly after the explosion but did not meet the criteria (very specific criteria). For us, it was just another degrading situation that we all keep finding ourselves in, having to justify to those in authority how our lives have been affected since the explosion in order to apply for help. We spent over 12 weeks at the B&B, paid for by our insurance [after which we] were literally left floundering alone and told to find ourselves somewhere to live. I was sent to Wirral council offices and was told to declare myself and my family homeless in order to even be considered for housing help. We were homeless through the action of another and had lost everything we had ever known. We survived purely from the help of local people who helped us secure temporary accommodation after 3 months in the B&B.”

Statement 7: “We lived in temporary accommodation for 17 months. Lots of our belongings were no good after the ceilings had fallen down on everything. Thank god it wasn’t us they fell on, that’s all we ever say. So we had to get help from charities. Got lots of second-hand stuff to start again.”

Statement 8: After the explosion l was left with nothing apart from what l stood up in. I had lost everything. I was eventually allowed to return to my flat after it had been made safe. My flat had been looted. This was supposed to have been protected. One of the most important things in my flat were my tools. I was offered a job, but due to the looting l was unable to accept this as l did not have the money to go out and replace them. So not only has this explosion cost me a decent home it has also cost me employment. After a few nights at the guest house l was allocated temporary furnished accommodation by Social Services / Council. When l was offered my current flat l was given some new goods such as cooker, fridge, bed, bedroom furniture. I was not allowed a table and chairs as l was single and on my own, nor was l allowed a fridge freezer. My family started to help me to get a home together again by buying me things l would need for when l got a place of my own, they bought things such as toaster, kettle, iron, pots, pans, cutlery and many more items required for a home. If it was not for my family l would have nothing.

As I stated in my previous report (Grundy Ridewood, 2018), in my opinion, from having spoken to people, and having read every word of the personal impact statements detailing the truth of what the victims have endured, and having read the guidelines, it is obvious that responsibilities and expectations have not been met. Since the writing of that report, I have acquired the concrete evidence that supports that opinion.

3. Emergency Management and the Bellwin Scheme

Government guidelines for emergency management by local authorities were compiled and produced with specific reference to lessons learned from previous disasters. Thus, they stipulate responsibilities for best practice to ensure expectations of the affected community are met.

The Civil Contingencies Act 2004 (Fig. 3) (HM Government a, 2004) states that it is the statutory obligation of the local authority to plan for emergencies. This includes understanding of all statutory legislation and non-statutory guidelines, such as the application process for the Bellwin Scheme to cover potential costs of an emergency (Department for Communities and Local Government, 2017). Failure of Wirral Borough Council (WBC) to understand the Bellwin Scheme is a failure to fulfil its statutory obligation under the Civil Contingencies Act 2004

Fig. 3 Responsibility of local authorities to plan for emergencies (HM Government a, 2004)

The Bellwin Scheme guidance notes clearly state in section 21, that a local authority must make their application to government for assistance through the scheme within one month of the incident, and that it is wise to apply for the scheme even if it is not known, at the time of reporting, whether or not the threshold will be reached (Fig. 4). This gave WBC until 25th April to apply for the Bellwin Scheme.

Fig. 4 Bellwin Scheme guidelines state that a local authority should apply even if the threshold is not likely to be met (Department for Communities and Local Government, 2017).

Furthermore, the one-month spending restriction is not from the date of the initial incident, but as shown in Fig. 5, it is from one month after the incident is deemed to have ended or moved to the recovery phase which would have given WBC one month after the site was handed over to them by the police, therefore until 7th May 2017, in which expenses would qualify. This means, that WBC had no valid reason not to make the application to the Department for Communities and Local Government within the time scale specified in the guidelines.

Fig. 5 Bellwin Scheme guidelines state that the one-month spending restriction applies from the date an incident is deemed to end (Department for Communities and Local Government, 2017).

Instead, WBC did not even consider applying for the Bellwin Scheme until a motion to “think about applying for financial assistance” was passed at a council meeting on 10th July 2017 (WBC a, 2017). In that same meeting, WBC declared they had £770,000 in reserve for emergencies, and that they would assess “whether individuals affected need assistance from the £770,000 held by the Council for ‘Support and Assistance to Public in Need’” (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6 WBC meeting in July 2017 - Motion number 35: Support for New Ferry (WBC a, 2017)

Fig. 6 illustrates that in 2017 WBC held £770,000.00 in its reserve account specifically for the purposes of funding emergencies such as the New Ferry Port Sunlight explosion, which meant that they could have immediately covered the costs of the emergency up to £770k.

In 2017, the threshold for successful application of the Bellwin Scheme for WBC was only £494,426.00 (HM Government c, 2017). Exceeding this threshold would automatically have activated the Bellwin Scheme, had it been applied for, and the government would have reimbursed any expenditure over that threshold, if only WBC had applied for the scheme in the appropriate time scale.

However, WBC did not apply in time and therefore the motion to “assess whether a formal application for emergency financial assistance under the Bellwin Scheme is required” in July 2017 was an entirely pointless exercise, as indeed was the motion passed on 15th October 2018, when motion number 59 was passed, declaring:

“Given that it has taken some time to establish the scale of damage to people, business and property arising from the gas explosion in New Ferry in March 2017: This Council resolves that the Chief Executive makes representations to the Ministry for Housing, Communities and Local Government to reconsider the judgement that the Bellwin disaster scheme does not apply” (WBC b, 2018).

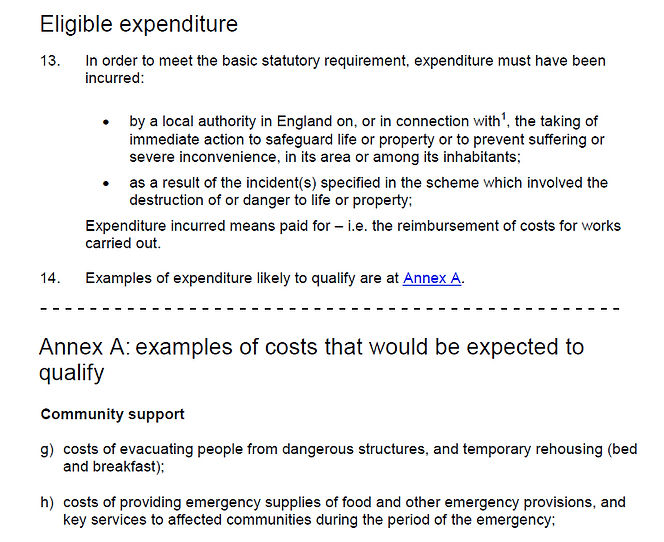

Furthermore, given the Bellwin Scheme specifically recognises that local authorities are obligated to assist the victims of disasters by paying for emergency supplies of food and other emergency provisions from their emergency budgets (Fig. 7), it has to be asked “Why did the council only consider thinking about giving financial assistance to the victims until after three and a half months had passed since the explosion?”

Fig. 7 Annex h of the Bellwin Scheme states that the costs of supplying food and other provisions to the victims is a valid local authority expenditure in the event of an emergency (Department for Communities and Local Government, 2017).

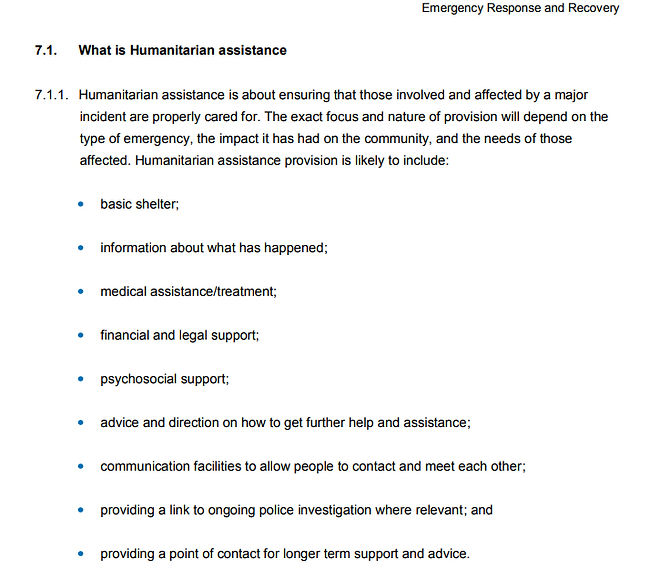

Not only is humanitarian assistance provided for in the Bellwin Scheme, but also it is adequately defined and considered in the government’s Emergency Response and Recovery guidelines (HM Government b, 2013). The definition of humanitarian assistance given on page 222 states clearly that it includes the provision of financial assistance (Fig. 8). It is also interesting to see that this 233 page government document defines “Impact” in terms of welfare and damage to the environment and does not consider the economic impact on governing authorities at all, and thus is contrary to the only methods used by both national government and WBC.

Fig. 8 Government guidelines define the terms of “humanitarian assistance” and “impact” (HM Government b, 2013)

As we can see in Fig 9, this same document states that humanitarian assistance in the event of a major incident should include the provision of financial and legal support (HM Government b, 2013).

Fig. 9 Humanitarian Assistance includes financial assistance (HM Government b, 2013)

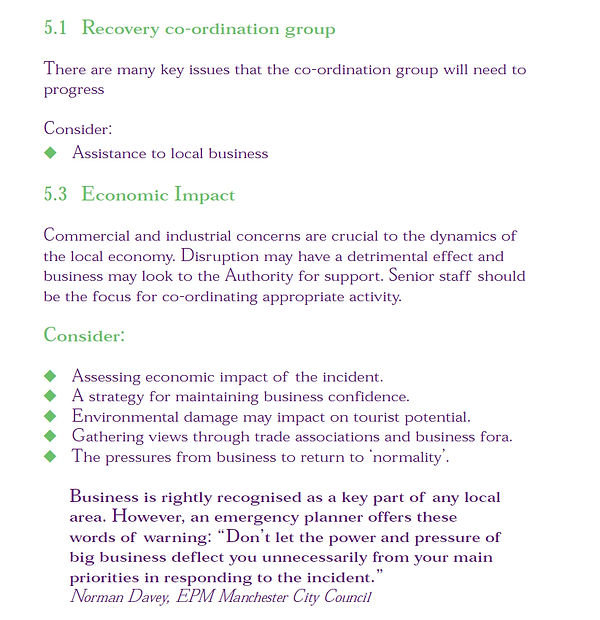

In their guidelines, government have also considered the needs of local businesses. Sections 5.1 and 5.3 of the Emergency Management Guide (Home Office, 2016) clearly state that the local authority must consider the impact of an emergency on the local business community. Considering that so many businesses were directly impacted by the explosion due to damage to their properties, and many more indirectly impacted by the closure of the shopping precinct in Bebington Road, quantification of the loss of trade should have been considered essential by WBC in order to fulfil the requirements given in the guidelines of “assessing the economic impact of the incident” as illustrated in Fig. 10.

Fig. 10 Due consideration should be paid to the impact upon local businesses (Home Office, 2016).

However, the only recognition of loss of trade came from the following public statement made by David Ball to local media on 14th June 2017, in which he stated "New Ferry has remained open for business throughout the recovery phase but we know that the closure of the road and restrictions on pedestrian access, which was unavoidable, has impacted on footfall and trade. I hope circumstances will now improve and I urge everyone to support their local businesses. We are continuing to meet regularly with New Ferry residents and businesses to update them on progress of the recovery operation and once again I pay tribute to their patience and resilience through these difficult times" (Manning, 2017).

So what did happen? According to all those impacted:

-

Victims made instantly homeless were left with no food, no clothes, no money and no material items. These were provided by generous families, friends and the local community.

-

Victims were advised by council to apply for means-tested state welfare in order to receive any assistance. Despite being made homeless by the explosion, some were not eligible.

-

There has been no contact from council with any businesses in order to quantify loss of trade.

On 10th December 2018, a new hardship fund was announced by WBC to assist the victims (WBC d1, 2018). At the council meeting that evening, in response to the question "Can you give us an update on what the council is going to be doing for New Ferry, please?" from Cllr Joe Walsh, Cllr Janette Williamson replied "In addition to the funding we've already invested there with regards to the clean-up post-blast which is over three hundred thousand, we've agreed in principal to set aside a separate hardship fund for those victims of the blast, which will be for New Ferry, only New Ferry, and that the criteria will be different to our other hardship funds such as the Local Welfare Assistance Fund (LWFA)." The pertinent part of the speech can be viewed on YouTube (WBC d2, 2018).

[The reasoning for the above last paragraph: since the purpose of the meeting on 17/06/19 aimed to prove to council cabinet members that the hardship fund was originally specifically designated to assist victims, something the new council had conveniently forgotten after the local elections in 2019, they needed this quick reminder written down.]

4. Council Expenditure

Under the Freedom of Information Act 2000, a full set of accounts were received in FOI Number 1342912 on 20th September 2018 (WBC c, 2018). The spreadsheet comprises five sheets: the first with a summary of transactions, the second with a coding summary, the third and fourth are entitled GL and AP and both detail individual expenses, and the fifth entitled AR details all reimbursements.

The expenditure items have been rearranged and grouped according to purpose, or spending category. Most of the expenditure items give enough detail to determine its purpose, or spending category, but where not specified, assumptions have had to made. Please see Appendix C for full notes on how the individual items have been categorised.

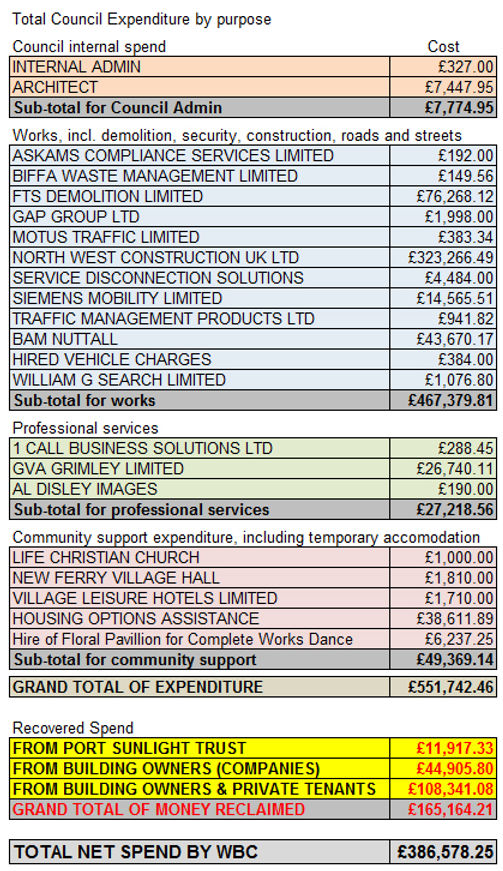

Fig. 11 Council Expenditure by category from FOI figures (WBC c, 2018).

Total expenditure by WBC for community support totals only £49,369.14, of which £40,321.89 was covering the expenses of providing emergency accommodation for some of those made immediately homeless. As we already know from the personal impact statements, some of the 78 made immediately homeless stayed with friends or family for some or all of their time following the explosion and were not given emergency housing by the council.

The payment to the Life Church was purely for the setting up of the collection / distribution centre for all the charitable donations that were generously given by the community and then distributed by willing volunteers who worked at the Life Church. The payment to the Village Hall covers hall hire costs so that representatives of the council could tell victims how to apply for means-tested help from the LWFA and for benefits from the DWP. Victims who were unable to attend the council meetings held at the village hall, received little or no advice.

The only business to have been financially assisted was Complete Works Dance, for whom the council generously waived the hire charge for the Floral Pavilion so that they could put on their summer show. Though this charge was waived, it was accounted for in the expenditure for the explosion above.

There are no other expenditure items what-so-ever for community assistance.

-

There are no emergency subsistence living payments given to any of the homeless victims.

-

There are no emergency welfare payments given to the injured victims and no costs for their assistance.

-

There are no emergency welfare payments given to those who suddenly found themselves without a job due to closure of their workplace, and for whom their employers could not pay wages during that period.

-

There are no emergency welfare payments to any business owners for loss of income or trade.

Wirral Borough Council have, on every single occasion that the New Ferry Explosion has been mentioned in media, categorically repeated that they have “already assisted the community to the tune of over £300k”. However, since waiving a fee does not constitute a real payment, of the total expenditure by WBC only £43,131.89 was actually spent on support of the community, and almost all of that was solely in the provision of emergency shelter.

All of the other stipulations in all of the government guidelines regarding the local authority’s responsibility to protect the welfare of the victims, to provide humanitarian assistance, to provide financial and welfare assistance have been ignored.

Also illustrated in Fig. 11 is the total expenditure which is £551,742.46. This total expenditure exceeds the threshold for the activation of the Bellwin Scheme. If WBC had applied in good time for the Bellwin Scheme, then they would have received financial assistance from national government. Furthermore, If WBC had assisted the victims of the disaster both materially and financially, as stipulated in all of the government guidelines, then their total expenditure would have significantly exceeded the threshold, although perhaps not to the maximum limit of their £770,000.00 emergency budget.

Government guidelines (Fig. 12) give advice to local authorities of the need to seek reimbursements for some of the costs incurred (Home Office, 2016). The very first point in the list is that the local authority should apply for activation of the Bellwin Scheme. The fourth point informs local authorities that they should “encourage those who have insurance to make the appropriate claims”, presumably so that the council could then recover any costs via third-party insurance companies.

“Recovered Spend”, i.e. reimbursements, is shown in Fig. 11 to total £165,124.61 and that these reimbursements have come only from the householders and building owners, including the Port Sunlight Village Trust. Given question four of the “pertinent questions which arose from the impact statements” (listed on Page 2) asked “what happened to the local community collections / donations that were handed in to council?” one might wonder, since there are no income details in the FOI figures, if WBC actually utilised point five of the reimbursement guidelines shown in Fig. 12. I have personally asked this question twice of WBC and received no reply.

Fig. 12 Government advice for local authorities on how to seek reimbursement of emergency costs (Home Office, 2016)

Full details, by invoice number, of the reimbursements are given in sheet five in the FOI figures. These have been rearranged into categories in order to make them more simple to understand who was charged, and these are summarised in Fig. 13.

Alarmingly, and in breach of Data Protection laws, sheet five had full names of all the individuals and companies who were charged reimbursements by WBC. I sincerely hope that this set of figures, bearing the names of the victims, has not been sent to any other enquirers. As with my promise of confidentiality for all those who wrote impact statements, I will not disclose this information and have now anonymised the figures. However, the knowledge of who was charged enabled me to conduct more research, since I have pertinent information in the impact statements regarding these charges and know many of the victims very well. This new research has enabled me to find out if those charged were actually covered by insurance. I do not know, however, if their insurance paid the council bills.

Fig. 13 Summary of reimbursements charged by WBC (WBC c, 2018)

Fig. 14 identifies that at least four of the victims who were charged reimbursements told me that they did not have insurance from which to claim.

Further research enabled me to acquire a second and different set of figures for the reimbursements charged by WBC. This second set of figures are different from the first. In most cases they are higher than the FOI figures (some significantly so), a few are the same, a few are missing from the second set altogether, and some are not in the FOI figures at all but appear in the new figures. Analyses of the figures does not explain why they are different.

Fig. 14 Analysis of the FOI and new figures for reimbursements charged by WBC

In some of the impact statements, and during some of the conversations I have had with the victims, I have been informed that the council bills for these reimbursements were threatening (e.g. “demanding money with menace”). Certainly, as the victims of such a devastating explosion which had left them with nothing and in serious debt, as well as suffering psychological impacts and depression, a demand from WBC for money of such large sums must have been exceptionally distressing.

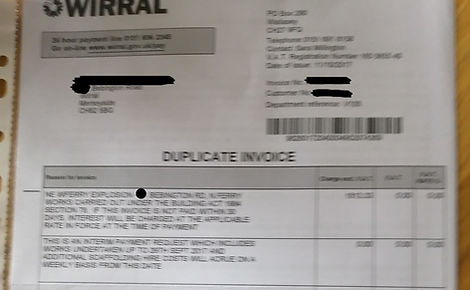

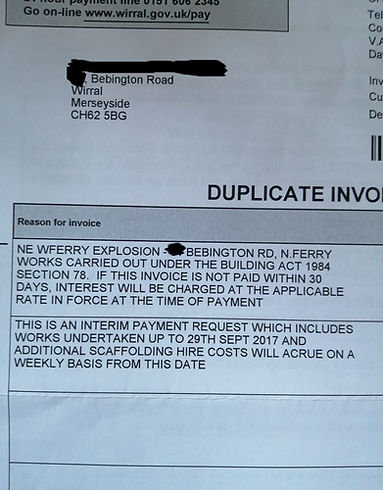

Many told me that they were angry that the charges had been forced upon them to have to pay directly themselves from their own pockets and wait for reimbursements from their insurers. Others told me that they simply had no money to pay the bills up-front, and had promptly passed them onto their insurance companies, only to receive a stream of bills threatening interest, court and bailiffs. Fig. 15 and Fig. 16 illustrate this to be true.

Fig. 15 Bills to victim 1 – Note that this is the first bill sent, and it threatens that interest will be charged if not paid in full within 30 days.

Fig. 16 Bills to victim 2 – please note that these bills had been sent promptly to the victim’s insurance company, who delayed payment such that the victim was threatened with court.

Given that the invoice numbers on the real bills that were sent to the victims of the explosion match those given on the FOI figures, it is also evidenced that the actual amounts charged to each payee were not those given in the FOI figures, but match those given in the new figures.

Therefore, the Freedom of Information figures as given on 20th September 2018 are not a true account of the expenditures paid and reimbursements charged by WBC following the explosion. If the only two sets of documents that I have obtained show values different to the FOI figures, then every single figure in those “official” accounts can not be trusted, and the true total of reimbursements received from victims is more likely to be £214,924.14. [Likewise the expenditure could be significantly different from that declared in the FOI figures.]

Furthermore, it is evident that, since the bills sent were indeed threatening, and since WBC sent bills to those whom they already knew did not have any insurance cover, WBC, in my opinion, paid no consideration what-so-ever to the circumstances of the victims. This is the furthest from humanitarian assistance that one could get.

Finally, it is in part, by sending these “malevolent” bills out to the victims, that WBC managed to reduce their total expenditure down to just £386,578.25 (or potentially only £336,818.32), the magic number by which WBC inform wider media on every possible occasion that they have supported the victims of the explosion. The statement usually reads “Wirral Borough Council have already spent in excess of £300k in support of the local community.”

So have WBC supported the victims? The evidence presented herein says “No, they haven’t”.

5. The New Hardship Fund

Having read the impact statements and written the follow-up report regarding the true humanitarian impact of the New Ferry Port Sunlight explosion, David Ball from WBC requested a meeting with me in October 2018. He stated that there would be a hardship fund for victims and asked me what was required of it.

I informed David Ball that WBC must fulfil their duty to assist the victims by:

-

Paying a one-time lump sum to every victim who was made homeless to cover their material purchases (such as underwear, outerwear, shoes, toiletries, over-the-counter essential medications and such like, because no person should be forced to wear second-hand underwear or be forced to beg for charity.)

-

Paying flat-rate subsistence living expenses to every person who was made homeless covering the number of weeks they were in temporary accommodation (commensurate with the victims of Grenfell, some of whom who were still in receipt of subsistence living expenses after 18 months)

-

Paying flat-rate loss of earnings to employees who did not receive any wages from employers (there are some) and to shop owners and workers who did not get any interim payments from DWP

-

Issuing of immediate refunds to all of the victims who had been charged reimbursements but had not received reimbursement from their insurance company (if one even existed).

David Ball asked me to work up a set of ‘ball-park’ figures on which the hardship fund could be based, which I did. I also talked about the reimbursements, and since many victims are angry with the council for having sent threatening bills, I advised David Ball that WBC must be extremely careful how they worded their letters of enquiry to every payee on their list of reimbursements, so that they are polite and potentially apologetic (for not having known that the bills were not covered by insurance). I offered to and did compose a ‘best-practice’ letter that WBC could use as a template by which to contact everyone (see Appendix D). I passed the draft ‘best-practice’ letter to David Ball and Neil Mitchell (also of WBC) on 29th October 2018. [This has now been revised – see Appendix D]

To this date, WBC have made no attempt to contact any of their payees to find out if those bills were covered by insurance, and thus WBC have actively chosen to continue to neglect their duty and their responsibility to their citizens.

Working with Cllr Jo Bird, my ‘ball-park’ figures were fine-tuned, and Cllr Jo Bird then wrote a proposal for council outlining the reasoning for and the method of distribution of the new hardship fund. The full document, dated and passed to council cabinet in January 2017, is given in Appendix E. [These figures have since been revised and match those in council’s press release dd 15/07/19]

In her proposal, Cllr Jo Bird outlines the best-practice methods for distribution, which is not means testing (which is already proven with at least one New Ferry victims not to provide assistance), and a method by which those who have suffered extreme financial difficulties as a direct result of the explosion will be able to reduce that debt by receiving that which they should have received immediately from WBC following the explosion.

The method set out by Cllr Jo Bird can effectively, quickly and easily retrospectively pay those costs to the victims that should have been covered by WBC’s emergency fund.

6. Conclusion

The new Ferry explosion was devastating, and the victims of this disaster should have been supported in many ways by their local authority. WBC failed in their duty to support the victims who should have fallen into a competent safety net, and as such WBC caused significantly more stress to the victims as a direct result of those failures.

Wirral Borough Council should view this hardship fund as a direct method of addressing those failures and a means by which to make amends and support the community whom they are obligated to support under the Civil Contingencies Act 2004.

Bibliography

Department for Communities and Local Government. (2017, October). The Bellwin Scheme of Emergency Financial Assistance to Local Authorities. Retrieved from https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/653402/Bellwin_Scheme_Guidance_Notes_2017-18.pdf

Echo, L. (2017, March 27). Timeline of explosion which rocked New Ferry. Retrieved from https://www.liverpoolecho.co.uk/news/liverpool-news/timeline-explosion-rocked-new-ferry-12805651

Grundy Ridewood, M. (2018, September 2018). The True Scale of the New Ferry / Port Sunlight Explosion. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=H9kuzYOW8fc (and also now on this website HERE)

HM Government a. (2004, November). Civil Contingencies Act 2004. Retrieved August 2018, from legislation.gov.uk: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2004/36/contents

HM Government b. (2013, October 01). Emergency Response and Recovery. Retrieved from GOV.UK: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/253488/Emergency_Response_and_Recovery_5th_edition_October_2013.pdf

HM Government c. (2017, October 23). Guidance Bellwin scheme: guidance notes for claims. Retrieved from GOV.UK: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/bellwin-scheme-guidance-notes-for-claims

Home Office. (2016, January 01). Recovery: An Emergency Management Guide. Retrieved from GOV.UK: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/62228/recovery-emergency-management-guide.pdf

Manning, C. (2017, June 14). New Ferry's recovery continues as cordon is reduced near site of devastating explosion. Retrieved from Wirral Globe: https://www.wirralglobe.co.uk/news/15347149.new-ferrys-recovery-continues-as-cordon-is-reduced-near-site-of-devastating-explosion/

WBC a. (2017, July 10). Agenda & Minutes Monday, 10th July 2017 6.00 p.m. Retrieved from Wirral Borough Council: https://democracy.wirral.gov.uk/ieListDocuments.aspx?CId=123&MId=5989&Ver=4

WBC b. (2018, October 15). Agenda and minutes Monday, 15th October 2018 6.00 p.m. Retrieved from Wirral Borough Council: https://democracy.wirral.gov.uk/ieListDocuments.aspx?CId=123&MId=7411&Ver=4

WBC c. (2018). New Ferry Explosion Expenditure FOI Number 1342912. Wallasey: Wirral Borough Council.

WBC d1. (2018, December 10). Agenda and draft minutes Monday, 10th December 2018 6.00 p.m. Retrieved from Wirral Borough Council: https://democracy.wirral.gov.uk/ieListDocuments.aspx?CId=123&MId=7412&Ver=4

WBC d2. (2018, December 10). Cllrs Walsh and Williamson talk about a new hardship fund. Retrieved from Wirral Council Webcasting - Transferred to YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eyuqeJh0i5M&fbclid=IwAR2PPK7ayPXXelXyzNb3n2oMb5usukFm_Dk4C2YAqHNrnokk7RDi5qP8pyU

Appendices

A. Photographs of destruction

Property 1: Amelia Jane Flowers, 37 Bebington Road. Florist shop fully prepared and stocked for the Mother’s Day trade, the single biggest event in the florist calendar.

Property 2: 5 Underley Terrace. This was home to a family, who were present at the time of the explosion. Two small children had just gone to bed upstairs. As you can see, the bedroom wall is demolished and the roof unstable.

Property 3: Griffiths Butchers, 68-72 Bebington Road. Thriving, long-standing business closed permanently. Building scheduled for demolition

Property 4: Lan’s House, 56-58 Bebington Road. Restaurant full, the night before Mother’s Day, including families with very small children. Completely demolished, everyone injured. The owner’s small children asleep in the flat above. The owners not given emergency accommodation.

Property 5: 51 Bebington Road. Home to a family with children and a pet cat.

Property 6: Ming Yuan Health & Beauty. 66 Bebington Road. Thriving business.

B. Personal Impact Statements

Reminder of published excerpts from impact statements

C. Council Expenditure – Details and Notes

D. Letter to those charged reimbursements

Original letter drafted October 2018

BEST PRACTICE EXAMPLE LETTER TO HOUSE OWNERS: (best practice is always to address victims of a disaster with care and compassion – Council has a responsibility to show duty of care – thus all correspondence should demonstrate compassion, a desire to help, and the means by which to help. In this instance, this letter should also contain an apology for the duration of time that has passed)

From Wirral Borough Council

Dear xxx

We are writing to you with regards to the charges levied by us on [date of demand letters] for security measures (boarding, hoarding, scaffold, 24-hour security) undertaken by us to protect your property following the explosion on 25th March 2017.

It was our understanding, having had lengthy discussions with and agreements from your insurance companies, that all of these charges would be covered by your insurers. However, it has recently come to our attention that some of your insurance companies did not reimburse some or all of these costs to you, as we expected them to do.

We are sorry that we were unaware of the negative financial circumstances that this may have caused and would therefore like to rectify this for you as quickly as possible.

If you did not receive reimbursement from your insurance company for the charges levied by us, and have had to personally cover these costs, then we would like to rectify this for you.

We will contact your insurance companies to ensure that this matter is addressed and rectified, with full reimbursement to you. Where any insurance company refuses reimbursement [on the premise of exclusion clauses / exemptions / any other excuse they may use], Wirral Borough Council will reimburse these costs to you.

Please complete and return the enclosed form, detailing [the costs that were not covered, the name of your insurers, policy number etc etc] and return it to us as soon as possible. The earlier we receive your response, the quicker we can rectify this for you.

Yours sincerely,

[Signee]

For and on behalf of

Wirral Borough Council

Revised draft letter written 20th June 2019

BEST PRACTICE EXAMPLE LETTER TO HOUSE OWNERS: (best practice is always to address victims of a disaster with care and compassion – Council has a responsibility to show duty of care – thus all correspondence should demonstrate compassion, a desire to help, and the means by which to help. In this instance, this letter should also contain an apology for the duration of time that has passed)

From Wirral Borough Council

Dear [ # insert name of payee]

We are writing to you with regards to the charges levied by us on [ # insert date of demand letters] under invoice number [ # insert invoice number] for security measures and / or for demolition works undertaken by us on property [ # insert property billed].

Firstly, we would like to sincerely apologise to you for any distress that receipt of these bills may have caused.

It was our understanding, having had lengthy discussions with and agreements from insurance companies, that all charges would be covered by insurance. However, it has come to our attention that some insurance companies may not have reimbursed some or all of these costs to you, as we expected them to do, and that some of you may not have had any building insurance policies.

We are sorry that we were unaware of the distress and negative financial circumstances that this may have caused and would therefore like to rectify this for you as quickly as possible.

- If you did not have insurance from which to claim, we would like to refund the costs to you immediately, or in the case of charges levied on land that are not covered by insurance, we immediately revoke these charges.

- If you had insurance but did not receive reimbursement from your insurance company for the charges levied by us, and have had to personally cover these costs, then we will contact your insurance companies to ensure that this matter is addressed and rectified quickly. In instances where insurance company refused reimbursement on the premise of exclusion clauses / exemptions / any other reason of their making), Wirral Borough Council will reimburse these costs to you.

We would like to resolve this for you promptly, so please complete and return the enclosed form and return it to us as soon as possible. The earlier we receive your response, the faster we can rectify this for you and provide all due refunds / revocations.

Yours sincerely,

[Signee]

For and on behalf of

Wirral Borough Council

These are the ONLY questions that need to be asked on the form:

Did you have building insurance for the above-named property on 25th March 2017?

No – We will issue a full refund to you immediately.

Yes – Did you receive full reimbursement of the charges levied by us from your insurance?

Yes – Thank you for confirming that our bill was covered by your insurance.

No – We will contact your insurance company to resolve this discrepancy and issue any refunds / partial refunds as applicable.

Please complete the following:

1. Name of insurance company:

2. Address of insurance company:

3. Telephone number of insurance company:

4. Insurance policy number:

E. Distribution of the Hardship Fund

Proposal for method of distribution of hardship fund, written and given to WBC on 20th January 2019. Please note that the figures have since been amended and match those in council’s press release dd 15/07/19

New Ferry disaster hardship fund

1. Council policy

Wirral Council unanimously agreed a motion on the ongoing impact of New Ferry explosion on 10 December 2018.

During the debate, Cllr Janette Williamson announced a new hardship fund for New Ferry. She said, “We have agreed in principle to set aside a separate hardship fund for those victims of the blast. Which will be for New Ferry, only for New Ferry. The criteria will be different to our other hardship funds, Local Welfare Assistance scheme.”

Cllr Jo Bird reported to Council, “Wirral has repeatedly sent detailed letters to government asking for help. The Council has spent £560,000 dealing with this disaster and reclaimed £215,000 in charge-backs to insurance, landlords, and residents.

The Bellwin disaster scheme should reimburse Wirral Council. But this government will only consider that, it seems, after the Council spends almost half a million pounds. So, there could be a gap of £183,000 for our Council to make payments to meet the government’s threshold - and help heal the wounds and transform the lives of devastated people and traders.”

Cllr Bird urged, “Fellow Councillors, please support this motion. Let’s take action, to find a way to make hardship disaster payments of at least £183,000. Let’s formally apply to the Bellwin disaster scheme and insist that the government honour their promise to help.”

Wirral Council unanimously resolved to “Submit a formal application for funding under the Bellwin scheme as soon as possible.”

2. Lessons from funds for other disasters

Regarding Salisbury and Belfast situations, the government chose to make “loss of trade” payments to businesses affected. This is outside of the Bellwin scheme and it is difficult to find more public details on distribution.

Best practice can be gained from disasters elsewhere. For example:

-

Grenfell fire. Hardship payments were made from the local Council and government. Including a £5,000 flat rate payment with no impact on benefits. https://grenfellsupport.org.uk/money-and-benefits/

-

Manchester Arena attack. £20,000 paid to bereaved families very quickly. Further payments to people physically and psychologically injured. See question 3 “what has it been spent on?” http://www.manchesteremergencyfund.com/faqs/

Best practice common features include:

-

Victims and survivors are put first

-

Payments are made on a flat rate basis

-

Payments are dignified and non-judgemental - not means tested nor linked to insurance or status

-

Payments are made in respect of children, to their parents/next of kin

-

Simple system - quick and easy to apply for

-

Information and advice is freely provided regarding any impact on benefits

-

There is clear and transparent governance and decision making

-

Some funding comes from the local authority

-

Official support is provided to charitable agencies distributing donations from the public

3. People directly affected by New Ferry disaster

So far, it is known that due to the blast, at least:

81 people were injured

78 people were made temporarily homeless for more than one week

32 business were closed behind police cordon, of which 7 were permanently closed

The total number of people may not come to 191 because some people were affected in more than one way.

Lists have been compiled based on multiple records, including council tax, local welfare assistance, google street view, contact with ward councillors, personal impact statements and local knowledge. There is probably around 5% margin of error for under-reporting.

47 people and organisations were sent bills, without accompanying written explanation from Wirral Council, totalling £214,924. These bills are cited by many people as causing reputation and relationship damage with the Council. It is not known how much nor how many bills were covered by insurance, and it may be unnecessarily complicated to find out. Much goodwill and trust would be restored with a simple disaster hardship fund.

4. Proposed New Ferry disaster explosion hardship fund

It is therefore proposed to aim to distribute as follows:

An estimated 10% of eligible people may choose not to apply, for whatever reason.

It is recognised that these payments may not fully meet the needs of affected people and businesses. Wirral Council has agreed to seek re-imbursement and further payments from national government.

5. Process

Promotion could be by direct mail to people known to the Council and other agencies, as well as through the media and social media.

The fund should have a very simple application process to check eligibility, focus payments to people/businesses that need it and reduce the risk of fraud. An application form could ask only for:

-

Names of people in household (for residents)

-

Address at the time and currently (for residents)

-

Company and trading name (for traders)

-

Preferred contact details

-

Bank account details to receive payment

-

Tick boxes for how affected eg had to move home, physical injury (severe/minor), psychological injury (with treatment received), loss of trade/income.

NB. If a person had more than one impact, for example made homeless and injured, they would be entitled to payments for each type of impact.

6. Decisions

Decisions could be made by a panel of Council officers and ward councillors, seeking external advice when necessary. Non-intrusive checks could be made with available records. Appeals could be made to a similar panel of people uninvolved at that stage.

7. Recommendation

It is recommended that the New Ferry disaster fund be set up using the principles above including:

-

Flatrate payments to people directly affected

-

Simple, quick and easy application process

-

Aim to distribute at least £183,000

-

Submit a formal application for funding under the Bellwin scheme as soon as possible, to national government

Cllr Jo Bird

20 January 2019